Culture

New book tells early-life story of Louis Kenoyer

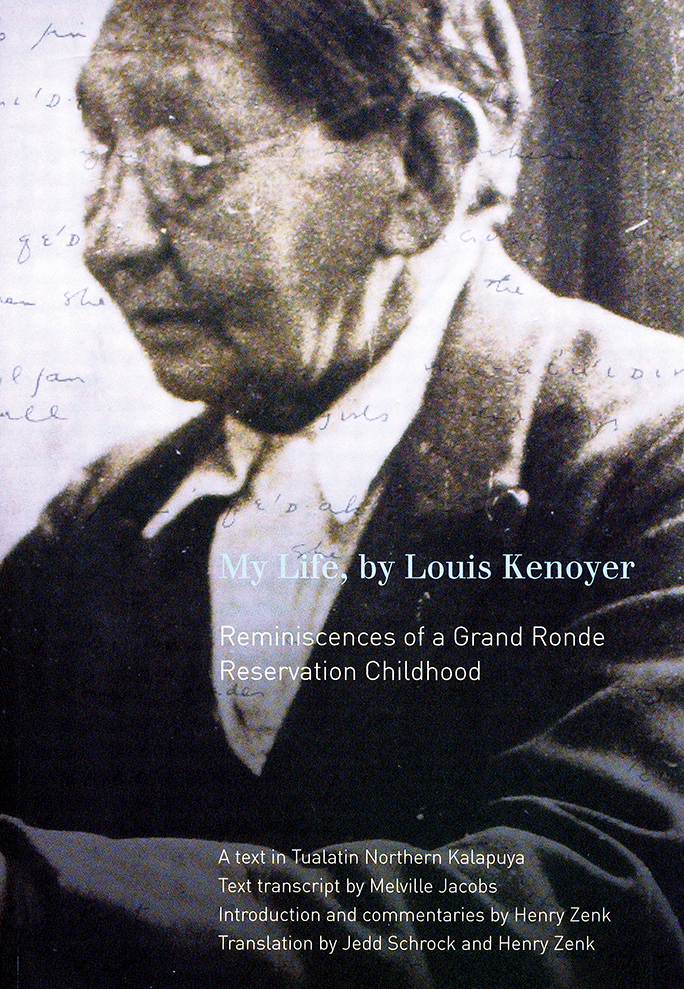

“My Life, by Louis Kenoyer: Reminiscences of a Grand Ronde Reservation Childhood”

Published: By Oregon State University Press in cooperation with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde

To order: Visit www.osupress.oregonstate.edu

Cost: $35

For approximately 51 years, Louis Kenoyer was truly unique.

He was the only person who spoke the Tualatin Northern Kalapuya language after his father walked on in 1886 and before his own passing in 1937.

Kenoyer’s first-person narrative describing life on the Grand Ronde Reservation in the late 19th century recently was published by Oregon State University Press in cooperation with the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde.

Titled “My Life, by Louis Kenoyer: Reminiscences of a Grand Ronde Reservation Childhood,” the book features a forward by renowned Oregon historian Stephen Dow Beckham, an introduction written by linguist Henry Zenk and 13 chapters of Kenoyer’s memories of growing up on the Grand Ronde Reservation presented in the original Tualatin Northern Kalapuya with an English translation.

“By his own account, his father was the last person with whom he spoke Tualatin,” the book’s introduction says.

Zenk, who has a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Oregon and has worked as a linguistic consultant for the Grand Ronde Tribe since 1998, first became aware of the Kenoyer narrative 40 years ago.

Kenoyer originally dictated the first part of his childhood narrative to Jaime de Angulo and L.S. (Nancy) Freeland in 1928-29 after Angulo drove him from the Yakama Reservation in Washington state to their home in Berkeley, Calif. Angulo was dispatched by Franz Boas, known as the founder of modern American anthropology, to find Kenoyer and document the threatened Native language.

The remainder of the narrative was dictated to Melville Jacobs in 1936 and Kenoyer died a year later before he was able to complete the translation with Jacobs.

Zenk found the transcript with the last quarter untranslated in the mid-1970s.

“I came across this autobiography during my earliest visits to the Melville Jacobs papers at the University of Washington archives,” Zenk said during the Wednesday, Nov. 1, session of the annual Grand Ronde History & Culture Summit held in the Tribal gym. “Over 40 years after I first came across it, it’s in print now.”

Zenk worked with Jedd Schrock, who has a master’s degree in linguistics from Northeastern Illinois University and specializes in Native languages of western Oregon and Washington, to complete the translation.

“The result is a complete bilingual English-Tualatin text, accompanied by extensive notes and commentary providing historical and ethnographic context,” the book cover states.

Zenk said that Kenoyer’s memories are an “important source” of information for any researcher interested in 19th century life on the Grand Ronde Reservation.

The cover photo of Kenoyer reading The San Francisco Chronicle was taken during his stay in Berkeley and was donated courtesy of Gui Mayo, Angulo and Freeland’s daughter.

Kenoyer was born at the Grand Ronde Reservation in 1868, a mere 11 years after President James Buchanan established the Reservation through an executive order.

Kenoyer’s father, Peter, came to the Reservation as an adult from a part of the Tualatin homeland that centered on Wapato Lake near modern-day Gaston. At home, Louis spoke Tualatin while at school he spoke chinuk wawa and English.

Angulo and Freeland turned over their Tualatin manuscripts to Jacobs, who started documenting the endangered indigenous languages of western Oregon when he joined the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington in 1928.

Jacobs’ work with Kenoyer in the summer of 1936 to go over Angulo’s and Freeland’s previous transcriptions and also to continue his autobiography ended when Kenoyer walked on in the winter of 1937, leaving the last quarter of the complete narrative untranslated.

“In the end, the passing of the language’s last known fluent speaker rendered this large chunk of the narrative, for all practical purposes, unusable to him (Jacobs),” Zenk writes in his introduction.

Zenk and Schrock learned to read Tualatin Northern Kalapuya from the previous translations and were able to translate 99 percent of the words and vocabulary appearing in the untranslated text.

Zenk says in the introduction that Kenoyer’s narrative “is an important addition to the record of this transformation” as Native Americans’ traditional hunting and gathering economies transformed to subsistence farming on the Euro-American model.

“With this shift of economy there came a wholesale adoption of Euro-American rural dress, housing, technology and work habits,” Zenk writes.

Comparing Kenoyer’s narrative with Jacobs’ accounts from John B. Hudson and Victoria Howard, two other Grand Ronde Elders, Zenk notes that “Kenoyer’s narrative adds a third perspective on daily life at 19th century Grand Ronde Reservation, one much more attuned to the meeting and inter-penetration of old indigenous practices and beliefs with newly introduced Euro-American influences.”

For instance, Zenk cites Kenoyer remembering a death in the family in which Catholic priest Father Adrien-Joseph Croquet and the Tualatin Tamanawas doctor Shumkhi both appeared.

Kenoyer recalls the event in the book’s second chapter:

“Then they sat in the house.

“One man, a half-woman named Shumkhi, a great Tamanawas doctor, her power was dead-people (Tamanawas).

“Then she ‘threw’ her song.

“She took five bundles of pitch sticks.

“She took one pitch bundle.

“Then she lit it.

“Then she shook it everywhere in the house.

“She drove away the dead person’s spirit-breath.”

Kenoyer and his younger sister were the only children out of perhaps 10 who reached adulthood. He moved away from Grand Ronde and boarded at Chemawa Indian School in Salem around the time his father died and eventually received an allotment in Grand Ronde in 1891.

He had two families in Grand Ronde. He had two boys and two stepchildren, all of whom died young. Sometime before 1914, he left Grand Ronde after the death of his second wife, ending up at the Yakama Reservation in Washington state.

He died, taking an indigenous language with him, on Jan. 16, 1937, at the town of Harrah, Yakama Reservation, from influenza.

Zenk said during the summit that the lack of knowledge about Kenoyer’s adulthood leaves him a “man of mystery.” “We don’t have much on Kenoyer … the man,” he said.

However, Kenoyer the Reservation child has been preserved, Beckham said in the book’s foreword.

“The autobiography of Louis Kenoyer is in a class of its own,” writes Beckham, Pamplin professor of History-emeritus at Lewis & Clark College. “It is one of the rare first-person narratives by a Native American discussing life on an Oregon Reservation. This volume rescues from obscurity the story of his life, conditions on the Grand Ronde Reservation, and, for the first time, completes the translation of his narrative from the Tualatin dialect of Northern Kalapuya into English.

“It is Kenoyer’s story recounted in the traditional narrative style of the Tualatin speakers of the northern Willamette Valley. The account covers the 1870s to the 1880s and provides a heretofore unavailable record of the forced acculturation and transformation of Oregon Indians from their traditional fishing, hunting and gathering cultures into sedentary agrarians speaking English and worshipping the deity of their conquerors.”