Health & Education

Panel addresses health inequities in Indian Country

By Danielle Harrison

Smoke Signals staff writer

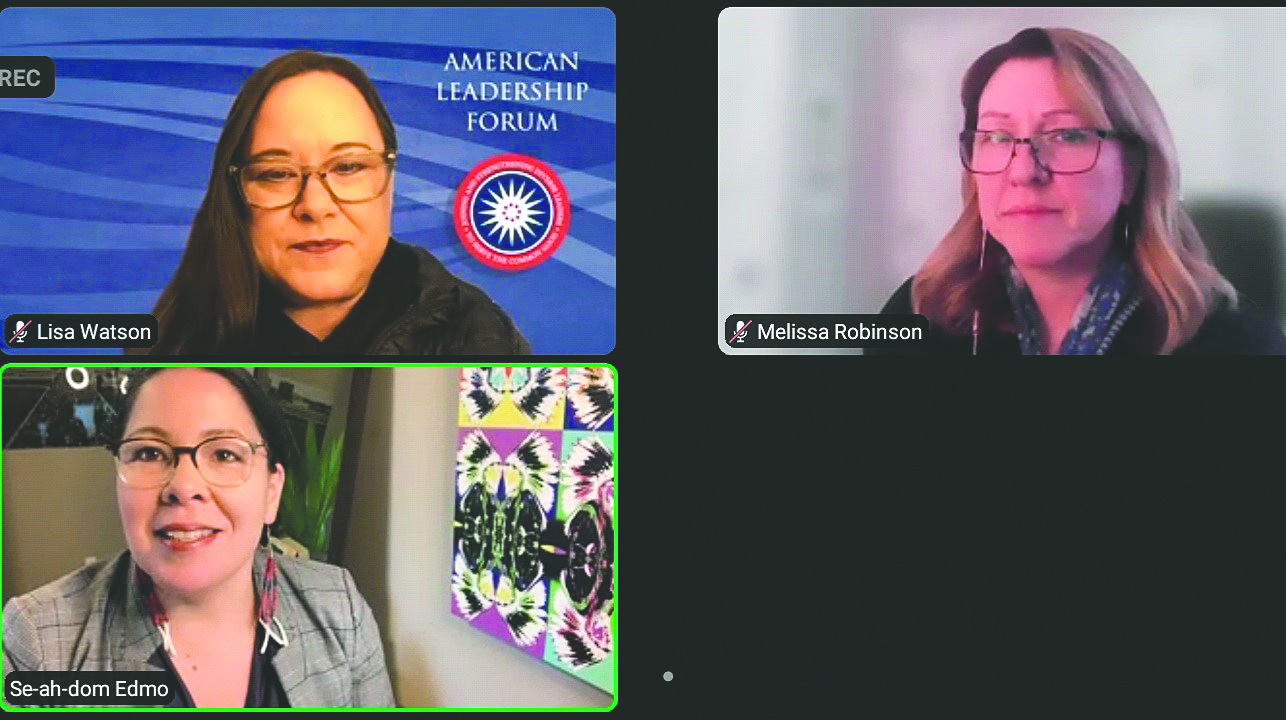

PORTLAND -- Tribal member and American Leadership Oregon Executive Director Lisa Watson led a panel discussion on health inequities in Indian Country in recognition of Women’s History Month.

The discussion, held on Thursday, March 18, via Zoom included Watson, MRG Foundation Director Se-ah-dom Edmo (Shoshone-Bannock, Nez Perce and Yakama) and University of Providence Nursing Division Chair Melissa Robinson (Salish and Kootenai).

The event was sponsored by Portland State University, the Center for Women’s Leadership and Tillamook.

“This is an important subject always, but even more so in this current time we are in,” Watson said. “I’m very excited to be here today to discuss health care as it relates to health inequities for Indigenous communities. … One of my leading values is once we know better, we must do better. I would invite the audience today to take this new information and turn it into action in your own communities.”

Watson’s first question for the panelists was their thoughts on the term “health inequities” versus “health disparities.”

“I’m not a health practitioner, but I love working on things,” Edmo said. “I love operationalizing our traditional values into how we do our work. For me, I much prefer the term ‘health inequities.’ Health inequity is something you must make equitable. Health disparity makes it seem like a foregone conclusion, that something is just the way it is.”

Robinson agreed.

“Disparity means different. We need to get away from that term. Health outcomes aren’t just different when something has been unfair or unjust. Health disparities is ingrained as a term in the health care system. In education, what I’ve learned is that as children and adults enter the system, the opportunities haven’t been equal. When we can create an equitable playing field, we will be better. It is not an easy thing to change, but I think we can.”

Added Watson, “It is important for us to have a shared understanding of a term that is so loaded.”

The next question involved the various ways Indigenous people access health care.

“For me, it is IHS (Indian Health Service) first,” Edmo said. “It is one thing that has been a common element of treaty and trust responsibility. We have to first fully fund IHS. Every time the budget comes up, the myth of scarcity does. How health dollars are managed has troubling reverberations throughout Indian County. Elders are very aware that this is the case. They will forgo care in case a younger family member gets seriously ill. These are upsetting dynamics.”

Robinson shared a story of her grandmother receiving a letter from Indian Health Service and worrying about what to do.

“The letter told her not to access care unless it was life threatening,” she said. “It was a hard budget year, but so scary for her because it limited her ability to access care. Another barrier is that since Indian people get free health care, it is hard to combat that with the qualitative experience of what it is really like. Being able to (raise awareness) and communicate that with people is an important starting point.”

Watson said experiences like that can be trauma triggers.

“It’s another communication that makes you fundamentally aware that you don’t matter,” she said.

The third question for panelists involved the value of having culturally specific health care.

Robinson said she considers designating something as culturally specific care can risk safety and quality by increasing stereotypes about what different racial and ethnic groups want, and hamper providers’ ability to offer individualized care and develop trust.

“If we can be humble about what we don’t know, that humility will help us listen, ask good questions and demonstrate trust,” she said. “Our identities are informed not just by socioeconomic status and educational level, but so many other different things. It’s important to recognize how broad those experiences can be.”

Edmo said she feels culturally specific care has value in the context of who someone is as a person.

“I absolutely believe that many of our communities experience their best health with eating First Foods and diets that have sustained people for generations, and within our extended family structures. I think culture should always be looked at as an accelerator to achieving health and wellness for individuals.”

Added Watson, “It’s a systems change question. How do we embrace the systems that are going to be affirming of all of our identities, and educate people not only to embrace but to work within these systems? It’s a tall order but it’s doable. These are things we can do.”

The last question involved trauma-informed care and the importance of being aware of it.

“More people have experienced trauma than have not,” Robinson said. “COVID is a level of trauma we haven’t seen in our lifetime. We need to provide an open level of understanding for people.”

Added Watson, “We could spend days or weeks talking about trauma. I think trauma-informed interaction is something everyone should be aware of.”

After the panelists finished answering Watson’s questions, they fielded three audience inquiries.

Center for Women’s Leadership Interim Executive Director Jessica Mole thanked panelists for their participation in the event.

“It has been really meaningful to be in a space with all of you today, hearing your experiences and learning from your collective wisdom,” she said.

Added Watson, “Thank you for the experience and for sharing your hearts today.”