Culture

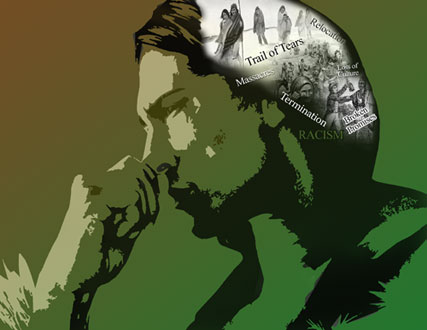

Effects of historical trauma affecting modern-day Indians

Life has been tough in Grand Ronde.

From the 1856 Trail of Tears onward, just about every generation has faced a trail of broken promises; law after law that told Indians they were not just different, but somehow not worthy of the same rights as the European settlers; and with that came a run-of-the-mill prejudice that affected almost every aspect of life.

"We were just those damn Grand Ronde Indians," said Tribal Elder and Tribal Council member Steve Bobb Sr. of his early life in Grand Ronde. "In Willamina and Sheridan, that was their attitude.

"As a kid, I remember every weekend there were wrecks out here. All the time. They were pretty much all alcohol-related, so I think that was a contributing factor, for sure."

Dottie Greene, an Elder of the Grand Ronde Tribe, remembers that when her father, former Elder Gus LaBonte, would be away on the job overnight, he made sure his wife barred the door for safety; and on the other hand, when he was at home, the slightest infraction, or the slightest perception of an infraction, brought on a painful and unjustified punishment.

"I had to go a quarter of a mile for water," Greene recalls, "and at night, it could be cold. One time, I wanted to get a wrap against the cold, and he thought I was talking back."

"It's just amazing how much trauma is here," said Tribal member and Behavioral Health Director Kelly Nelson. "The number we serve is only skimming the top, and I don't think the number is going down."

It wasn't always so clear that the first set of problems played a major role in the second set, but in the last 30 years Indian academics and behavioral specialists have come a long way and it is now taken as truth that the constellation of all of the physical and behavioral problems can be attributed to long-term mass trauma, also called Historical Trauma or Intergenerational Trauma because it is passed down through generations. The latest generations don't even have to have suffered the original trauma to experience the effects.

The telling difference between historical trauma and ordinary trauma, said psychologist Clay Mathewson, who worked in the Tribal Behavioral Health unit in the 1990s, is that "people who were in Vietnam or (Hurricane) Katrina, they know something has shifted, but when the trauma is historical, going back generations, not having your emotions, or being overwhelmed, becomes the norm. They don't even know there's something going on."

To the extent that the drivers of these intergenerational traumas are intentional, reported Mitchell M. Sotero in a 2006 paper in the Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, they "threaten basic assumptions about an orderly, just world and the intrinsic invulnerability and worthiness of the individual."

"What is trauma? And what isn't?" asked Leslie Riggs, a Tribal member and supervisor of the Voc Rehab 477 Program at the Tribe. "Am I distant and detached because that's my nature? Or because I suffer from historical trauma?"

"I know what Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) stands for," he said, "but maybe not how it informs my behavior. Maybe we can't know, but that doesn't mean we can't ask questions."

"There's more work to be done," said Kevin Gover (Pawnee), currently director of the Smithsonian Institute's National Museum of the American Indian and assistant secretary for Indian Affairs in the Department of Interior during the Clinton administration, "but there is no doubt about how real it is. There's a lot of reluctance to acknowledge it, and that is bound up in not wanting it to become an excuse for any failings we have."

Indians in Grand Ronde and aboriginals around the world are not alone in experiencing historical trauma. It is a disease of the colonized, enslaved, and victims of war and genocide. The problems come from all the major institutions of any society: religion, government, medicine and industry. But the solutions, specialists say, start in the community.

For the western world's indigenous peoples, current historical trauma was set in motion by the Papal Bulls of the late 15th century, when the Catholic Church followed by the Church of England - seeing European explorers venturing into what was wilderness to them - codified the idea that it was okay to make the indigenous of the world subservient. Just as conquering the land enabled the spread of European monarchies, conquering the people enabled the spread of European religions.

The Episcopalians (the Church of England in America) repudiated this policy in 2009. The Catholic Church has yet to repudiate it.

If much of the problem, from the 19th century, was intentional, the starting place and the biggest insult of all came from European diseases that decimated the forebears of the Grand Ronde Tribe. From 160,000 in the 1700s, their numbers had fallen to 40,000 when Lewis and Clark came through and to 2,000 by the 1850s when the Natives of Oregon were marched to reservations.

"That's an awful drastic blow on the population," said former Tribal Elder Merle Holmes to a 1976 federal task force, Task Force Ten, charged with investigating the lot of Terminated Tribes.

These losses made all that was to follow so much harder to bear.

Many historical events starting in the time of the treaties held sway up to Termination and beyond.

"One traumatic set of events of the time are the volunteer militias of southern Oregon and northern California," said Tribal member David Lewis, director of the Tribe's Cultural Resources Department. "This was a major period of events where whole villages were massacred by whites, and many of the dance houses were burned to the ground with hundreds of people inside. A true holocaust according to the definition in the dictionary. The period lasted from about 1850 to 1860.

"Volunteers were settlers and gold miners and farmers who sought the complete extermination of the Indian people of the region. This was all related to racism, prejudice that followed Indian people to the reservations and was still a common presence when Termination released everyone into society. My father told me that when he grew up it was a time of racism for Indians, which is reiterated by Don Day for his youth in Salem. In some areas, like southwest Oregon, that history of conflict is still raw even today."

Psychologist Joe Stone, Ph.D. (Blackfeet), director of the Grand Ronde Tribe's Behavioral Health unit from 2000-06 and currently director of Behavioral Health at the Indian Health Service in Gallup, N.M., published his first major paper on historical trauma during his time here.

He named U.S. federal policies of assimilation among the causes:

- Loss of land;

- Imposition of an unnatural social order;

- Suppression of language, ceremonies, culture and spirituality;

- Destruction of indigenous family systems;

- And denial of the historical importance of Native Americans.

The actual policies responsible included:

- The 1850 Donation Land Act that encouraged settlers, by offering free land, to move west into local Tribes' hunting and fishing grounds, and thereby also took away prime meeting and trading places;

- 1855 treaties that took away, among many Native peoples, Oregon Indian rights to lands between the coast and the Cascade mountain ranges;

- Trails of Tears: 1856 removal of Indians from their homelands to the Siletz, Grand Ronde and other Oregon reservations;

- The General Allotment Act of 1887 that converted 33,148 acres to individual allotments to open a path by which the land would go from Indian trust land to taxable (fee status) land after 25 years. The act fostered a huge transfer of reservation land from Indian to non-Indian owners;

- The 1901 Congressional Act that ceded 25,791 acres, nearly half of the Grand Ronde's reservation, to the public domain in 1904. Declaring it surplus, the federal government sold it, mainly to non-Indians;

- The Termination Act of 1954, which, in Grand Ronde's case, took away all Tribal land but the small cemetery, and ended treaty guarantees of housing, education and other basic needs in exchange for the rights to own the land Indians had used from time immemorial, back 11,000 years at least.

Merle Holmes, referring to the 1901 Act ceding 25,791 acres to the public domain, told the task force, "The United States, we feel, acting as trustee for the Indian people, were pretty negligent and didn't act in the best interest of the people they were representing as this particular section of land took away the wealth of our people, both past and present."

"I could tell my dad felt it," said Jim Holmes, a member of the Tribe and Merle Holmes' son. Jim and his brother, David, also a member of the Tribe, "had a real easy childhood," he said, living in Salem, away from the reservation, and so felt no ill effect from the big traumas that their father was describing to the federal task force. In fact, what Jim saw was just the little things.

"I think that he felt that people kind of talked down to him. It would be little things, like at the grocery store, they would say, 'This costs a little more,' as if he couldn't afford it."

Termination as the centerpiece

The centerpiece of historical trauma in Grand Ronde was Termination. It ended any pretense of promise or debt by the federal government to the Grand Ronde people, and treated Tribal heritage as a throw-away commodity.

"With Termination," said Tribal Elder and former Tribal Chairwoman Kathryn Harrison, "came a pain in your heart that never goes away."

In what at the time may have been a new low in political cynicism, U.S. senators sold Termination legislation "as a method of making the Indian equal before the law," according to the Task Force report.

While President Dwight D. Eisenhower pledged in his 1952 campaign to have "full consultation" with Indians on federal Indian policy, according to the Task Force studies, only about 16 percent of western Oregon Indians understood that the Termination of 1954 meant loss of treaty-promised federal services. Seventy-four percent said later that Termination legislation was passed completely without their knowledge.

To those that approved the legislation, it was sold as a way to give Indians small financial windfalls due from successful lawsuits against the federal government. Those windfalls needed enabling legislation to distribute per capita payments. Authority to distribute these funds was tied to the Termination bill.

Interior Secretary Douglas McKay, a former Oregon governor, played Sen. Joseph McCarthy's Communism card, calling Tribal identity "socialism," and pitted it against the spirit of individual capitalism.

Kathryn Harrison remembers Termination coming this way: "The people from the BIA came here and said, 'You might as well get used to Termination because it's coming anyway.' "

At the same time, said David Lewis, former Tribal Elder Abe Hudson was working at the state Capitol. "He used to listen in and then they'd talk about it here (in Grand Ronde)."

Grand Ronde Tribal Chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy was a child when the prospect of Termination first appeared on her radar in Grand Ronde. Her understanding of it came from what she could glean from her parents and other adults in the family.

"Children are so wise," she said, "and they know if you're afraid. They can feel it. Your words can say, 'It's okay,' but children can look in your eyes and see that it's not okay.

"As an adult now, knowing what I know, I'm less fearful. I'm feeling more secure and confident that principles like perseverance, hard work, integrity and honesty will bring to fruition what you are attempting to do."

While housing promises had come and gone over the years, the federal government never delivered much in the way of health care or education either to Grand Ronde, even before Termination, ironically leaving many without a clue that anything had happened.

Before or after Termination, said Tribal Elder Dale Langley, "I don't remember any difference."

"The medicines the federal government provided Indians in the 1850s were still there in the 1890s," said David Lewis.

"(Tribal Elder) Nora's (Kimsey) mother was paralyzed," recalls Tribal Elder Leon "Chip" Tom, "and she was always in a rocking chair. They didn't have a wheelchair, so they pulled her around in the rocker."

"I cut my foot swimming in the river," remembers Langley. "The next day, they took me up to the community hall (where the doctor was) where Verna Larsen used to live. They didn't have any pain killer. They just held my arms and legs, and she put some stitches in."

Usually, if he cut himself, he said, his folks just put turpentine on it and sent him back out to play.

In the 1930s, recalls Kathryn Harrison, "They gathered kids at the different reservations and took them to Chemawa (Indian School where there was an Indian Health Service outlet), and they took their tonsils and adenoids out if they needed to or not."

When Chip Tom was 10 or so, his folks brought him in. "I saw that bucket there filled with bloody tonsils," he said. "I didn't know what to think."

The same was true of dental care. "It was real poor," remembers Tribal Elder Margaret Provost. "They didn't fix your teeth. They just pulled them."

"That was the thing that inspired me to work for Restoration," Provost said.

Tribal Elders remember that after Termination, the government, even at the local level, continued to resist giving Indians good health care. The principal at one school was a good example.

" 'You let one Indian through and they'll all expect it,' " a Tribal Elder recalls him saying.

Time and again, though, Indians fought the neglect. Kathryn Harrison remembers former Tribal Elder Eula Petite, who was a teacher for many years in Grand Ronde, standing up to authorities.

"The doctors came to the school," said Harrison, "and she told them, 'You're not going to treat just the white kids.' "

For all the fight, though, the public neglect took its toll on Indian families. Early on, for example, Tribal Elder Nora Kimsey was one of four children out of 12 who survived childhood.

And today, tragic statistics for disease and social difficulties among Indians far outstrip any other ethnic group. The Indian suicide rate in 2005 was twice the national average.

Side effects of federal policy and practice included distrust of the colonizer. Generations out, the trauma continues and so does the distrust.

"We flat didn't go to the doctor unless we were dying," said Tribal Elder Gladys Hobbs, who was 10 years of age at the time of Termination.

"So many doctors, dentists and professionals at Indian clinics are white," said Joe Stone, and without referring to their trustworthiness, he noted that still today they are not trusted by Indians.

He spoke at a 2010 conference, International Network of Indigenous Health Knowledge and Development, held at the Suquamish Nation in Washington, with his front tooth missing.

The many faces of Termination

Termination had many faces, though. It also was a time when federal efforts to mainstream Indian populations played out with job opportunities and financial assistance becoming available. It encouraged off-reservation jobs and opportunities.

Denise Harvey's mother, former Tribal Elder Maxine Leno, went to Nevada in search of federally provided opportunities and then, in the Bay area, she attended beauty school.

"While everybody was learning in school that women don't have rights and can't get jobs," Harvey said, "Mom owned a beauty shop (through BIA programs)."

"I took everything they offered," Leno told her daughter.

"Everybody started moving away," remembered Margaret Provost. "They had to for the jobs, and they went all over the U.S. It just wasn't the same out here. Few people stayed."

Ultimately, Provost herself, who turned out to be a prime mover in the Restoration effort, also moved away to find work.

"(Some) Indians developed a culture to survive the neglect," according to David Lewis. "Men took up logging and women took up agriculture," principally running farms and large gardens. They also harvested other folks' crops.

The Depression, for example, was not a bad time for many in Grand Ronde. Dale Langley is not alone in saying he was never hungry growing up. "I didn't know what the Depression was," he said. "My grandfather had milk cows and a garden, chickens and rabbits, and he sold calves for deer meat."

Understanding how historical trauma works

The loss of land, language and culture, the uprooting of family life and meaningful work among parents ends up preventing infants, in psychological terms, from "regulating arousal," in Joe Stone's words; or said another way, children with parents who are not in control of their lives or emotions also grow up without self-control. Without self-control, self-confidence is impossible. Without self-confidence, resilience to difficulty fades.

Cheryle Kennedy says historical trauma "masks itself in over-indulgences, abuse and materialism. I relate it to being non-productive."

"The power you feel when you feel that the whole community wants you to heal, it is incredible," said Donald Warne (Oglala Lakota), executive director of the Aberdeen Area Tribal Chairmen's Health Board and university level teacher of Indian Health Policy. "We walk with all our ancestors and all our people. Knowledge is never lost. It keeps coming back."

Others see healing as not getting rid of the trauma but a process that Indian people had to go through. "There are greater forces out there that determine our purpose in life," said Leanne P. Hiroti, a Māori specialist in fertility and reproductive issues in New Zealand.

Cheryle Kennedy counters despair with optimism, hope and faith that things can be better.

"You're looking out at the future," she said, "and thinking, 'I've got to work harder, be more educated, more prepared,' so (to fight this) maybe our standards are higher.

"But," she says, "even though there's always the discomfort, you can't let it consume you. You've got to see it for what it is."

One part of the solution, from White Bison, sponsor of the Wellbriety Training Institute, "is about learning how to grieve," said Marlin Farley, of the group.

Longtime Grand Ronde Tribal Vice Chair Reyn Leno recalled that his father, former Elder Orville Leno, "was very angry. Every time we did something with Chemawa, he'd say, 'Why do you support that now? I ran away from that place three times.' That was a difficult one. He had a severe hatred of the government.

"I always try to look for some good out of the bad. I think you'll find with Indian people, it's hard for them to forgive and it's easy for them to be angry; but if you stopped and dwelled on the past, you could be angry for the rest of your life, but does that do you any good?

"You can use these things as lessons, or you can sit and dwell on it and go in circles."

Academics began publishing papers on historical trauma in the 1980s, led by original work from Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart of Columbia University in New York. Her research mirrored work in the behavioral medicine establishment that in 1980 added PTSD to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Before that, the idea of naming the problem, no less treating it, was unspoken. One of the mantras of treating historical trauma today is: If you can't name it, you can't treat it.

Though historical trauma still has not made the list, it has definitely been named.

Listed or not, Stone says, clinicians ought to recognize the syndrome and incorporate the underlying symptoms into a diagnostic and treatment criteria for indigenous patients.

"When people come to you," said sociologist L.B. Whitbeck, a leading voice in historical trauma circles from the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, "half of the job is already done."

Efforts to treat trauma, whether from a single trauma or intergenerational, are finally under way almost everywhere in indigenous communities. Conferences fostering locally derived solutions are bringing together indigenous academics from all the English-speaking nations with significant indigenous populations: New Zealand, Australia, Canada and the United States.

"We don't take the answers to the community," said Stone, "because you know what? We don't have them. The community has the solutions."

Some of the damage may be seen in physical, possibly permanent changes, according to a 1997 paper published in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences.

"Evidence points to demonstrable neurobiological changes in the brains of individuals with PTSD, such as hippocampal atrophy, amygdaloidal hypersensitivity or Hypothalamic - Pituitary-Adrenal Axis dysfunction thus giving neuro-biological correlation to the effects of psycho-traumatisation."

"Our communities want us to be more than researchers," said Australian Clive Aspin (Ngati Maru). "They want us to be activists."

Among the activities required for building resilient indigenous communities, said Linda Tuhiwai Smith (Aotearoa - New Zealand), a leading Māori academic based at the University of Waikato in New Zealand, should be "building capacity, networking, and emphasizing the challenges and joys of community."

She called those indigenous peoples suffering with intergenerational trauma, "the marginalized of the marginalized."

Bonnie Duran, associate professor at the University of Washington's Department of Health Services and another leading academic, focuses on post-colonial approaches to social problems in Indian Country. "We shouldn't even be engaging with colonial language," Duran said. Indigenous approaches that are Tribe-specific and nuanced are more advanced.

There may be an urgent need for transformative change, said Joe Stone, but there are no quick fixes. "If we do our job well, in two generations there will be measurable results."

Black Elk, the famous Oglala Sioux leader, saw healing coming seven generations after Wounded Knee. That is the generation of today.