Culture

New courses teach Grand Ronde culture to employees

In the first of four classes planned for this and future years, Tribal Land and Culture Department staff members summarized some of the details of Grand Ronde culture, language and history.

Two one-hour sessions at the Community Center on Thursday, March 13, one repeating the lessons of the other, served almost a third of the Tribe's more than 300 governmental employees.

Tribal drums ushered in the program, which is primarily intended as a new employee orientation, but all were invited.

Cultural Outreach Specialist Bobby Mercier explained drumming and song protocols.

"In the early days of the reservation, in the 1860s when ghost dancers were here, we used square drums. We only see them today," he said, "at games, gambling and similar events. Today, it's mostly round drums."

The song that opened the program and many others, he said, is a song about and titled "New Beginnings."

"We have song recordings from the 1800s," Mercier added, "but we don't sing them because they belong to others." One needs permission to sing songs written by others, he said. One could buy them, not for money, but by laying gifts at the feet of the families of those who wrote them. Acceptable gifts include traditional foods and crafts.

Mercier also talked about smudging, burning sage, as a way of cleansing an atmosphere for "people who have a heavy heart." Some sage, also called mugwort, grows in Oregon on the banks of the Willamette River.

Cultural Education and Outreach Program Manager Kathy Cole took the groups through an elementary lesson in Chinuk Wawa.

The language has been a mainstay for the Tribes and bands making up the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde since the 1850s when approximately 30 different groups, each with their own language and culture, were herded and marched north to live together in Grand Ronde. Chinuk Wawa was the one language that all understood, at least a little, Cole said.

The lesson included Chinuk Wawa words for I, me, my, you, yours, how are you? what's wrong? and more.

She invited all to attend Chinuk Wawa classes Wednesdays at noon at Chachalu, the new cultural center and museum.

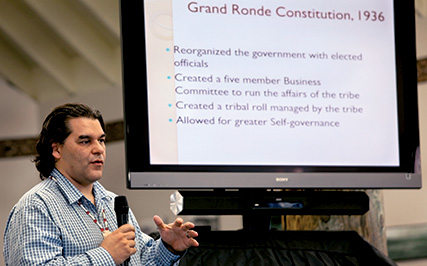

Tribal Historian David Lewis came with an eight-page written history of the Tribe, passed out to those attending, that noted important moments and milestones in the Tribe's history, going back some 13,000 years, or "before memory," Lewis said.

Much of the history came from the period following the Tribe's 1853-59 treaties with the federal government.

As a result of the treaties, the Tribe ceded more than 14 million acres, virtually all of western Oregon, to the federal government. In return, Tribal treaty signers were promised a place to live, food, schooling and health care.

"Most of us here have five or more ancestors from this group," Lewis said.

Indians were harassed by settlers during the 1856 Trail of Tears. Many thought Indians should be exterminated, Lewis said.

A year after the Tribes and bands arrived in Grand Ronde, the reservation included 61,440 acres of former land claim allotments that the U.S. Army purchased from settlers. By the turn of the 20th century, much of that land was declared surplus and purchased by the federal government, much of that sold at fire sale prices to timber interests that still own and harvest the trees on that land today.

Lewis also talked about the high land at Fort Yamhill, where Indians who were to become members of the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde were held, like in a prison camp. The high ground, with a view in every direction, served both to keep Indians in and settlers out.

When problems of Tribal peoples were not solved by government programs, the federal government's solution was to abandon the treaties. In 1954, the federal government terminated recognition and all promised support for the Grand Ronde Tribe, among many.

In 1983, federal recognition was returned to the Grand Ronde Tribe, but it came with new costs. The Tribes had to give up their hunting and fishing rights.

Later, almost 10,000 acres of the original reservation were returned to the Tribe. Later still, the Tribe began managing its forest land. The once great Indian culture that had withered with European contact began to rebuild itself in Grand Ronde.

Remaining trainings for the year will cover hair, regalia, carving and powwow protocols; plankhouse and sweat lodge protocols, along with Tribal ways of feeding the spirit; and water, first foods and first fish ceremonies.

"It's important for Tribal employees to understand the (confederated) Tribes, their people, their traditions and their world view," said Tribal Planner Rick George after the session. "This training is a great way for staff to get an introduction to the people they work for and with, and to better understand how their work connects to the cultures and traditions of the Tribes."

Tiffany Mercier, secretary in the Youth Education program, said she was "thrilled" to participate. She said she had "done all I can to jump into learning as much as possible about Grand Ronde history, culture, traditions and language. I feel that as a newcomer to the community, spouse, parent, Native and staff member - it is not only my privilege and honor, but my duty, to learn as much as possible."

"Being from another Tribe, Coquille," said Julia Willis, grants coordinator for Spirit Mountain Community Fund, "I was very interested in learning more about CTGR culture and history, especially since so many Oregon Tribes share common experiences.

"I always enjoy the drumming and songs, and really liked learning some Chinuk Wawa although I am not very good with that barred L!"

The program master of ceremonies was Land and Culture Manager Jan Looking Wolf Reibach.

"We're all connected," he said. "Tribal members and staff. All of us contributing to the Grand Ronde culture. As I see many Elders and others here who have a vast knowledge of Tribal culture, the broad range of traditional practices, songs and lifeways, I recognize that we're not teaching our culture. We're sharing what we know.

"The heart of our culture," he said, "is in people, not programs."