Culture

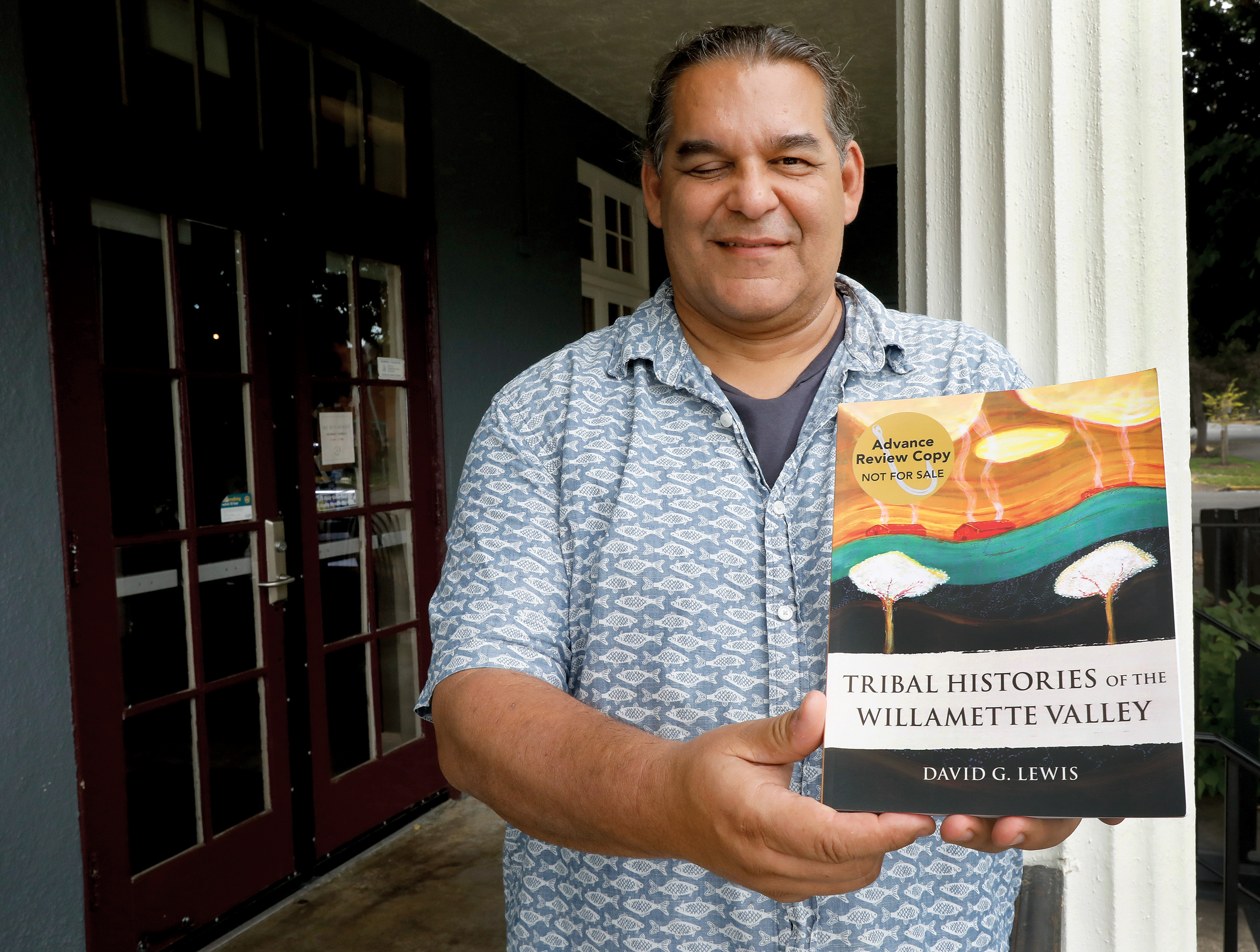

David Lewis writes histories of Willamette Valley Tribes

By Dean Rhodes

Publications coordinator

SALEM – Former Tribal Historian David Lewis sits inside the IKE Box Café, his ever-present laptop computer to his left.

He’s just a few blocks from the state Capitol, which is adorned with an 8.5-ton bronze sculpture with gold leaf finish of an Oregon pioneer that honors the European settlers who poured into the Willamette Valley in the mid-19th century and stole Tribal peoples’ land, displaced those Natives who survived disease and starvation to Reservations, and at times killed Tribal peoples for just trying to survive on what had been their ancestral homelands.

It’s a disturbing history that is told well in Lewis’ immensely readable new book, “Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley,” which will be released on Nov. 14 by Ooligan Press.

Although the old adage, sometimes attributed to English Prime Minister Winston Churchill, states that history is written by the victors, some 170 years after European settlers invaded the Willamette Valley and made it their own, the other side of the story is being told in greater depth and detail by Tribal descendants.

Lewis, 58, is an assistant professor of Anthropology & Indigenous Studies at Oregon State University in Corvallis and has been researching and writing about Willamette Tribal history for years.

His new 240-page book takes a deep dive into the separate stories of the numerous Tribes that eventually confederated and ended up at the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation in the mid-1850s.

“I dedicate this book to the Tribal People of Western Oregon, who deserve to be told the truth about their history,” he writes at the beginning of the book.

The book also includes information that rewrites many of the facts currently told about the history of Willamette Valley Tribes. For instance, instead of eight people dying and eight children being born on the Trail of Tears march from Table Rock to Grand Ronde in early 1856, Lewis found that the actual number was only seven on both accounts, according to the journal of removal.

“After I left the Tribe back in 2014, I started doing a lot of research on Tribal history,” Lewis says about the genesis of the book. “Not just at Grand Ronde, but all over … all of the different Tribes of western Oregon.”

From that research, he started writing the histories, eventually compiling more than 500 essays.

“So I decided to take those essays and just reformulate them into chapters in the book,” Lewis says.

The essay approach makes “Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley” imminently readable as people are able to consume the information in small bites and are not forced to read 20-page chunks of information in one sitting.

Lewis said he is hoping the book can be used in high school history classes as well as his own Kalapuya Studies courses taught at Oregon State.

“When I came into Grand Ronde, there really wasn’t a good history of the Tribe,” Lewis says. “So I developed that along with people like Eirik Thorsgard. We helped develop that history and since then I have been adding to it, adding more pieces to it. What I have discovered through my research is not just for my Tribe, but all the Tribes, they’re not really well researched or written about. In fact, some of the histories may be wrong.

“I think (the book) fills in more of that history of colonization because most of the books about the Tribes are about either the Kalapuyas in the past or don’t really follow the Tribes into the late 19th or early 20th century. I follow them into the events that were occurring in the midst of colonization and just after colonization, and what happens on the Reservation.”

Lewis’ book paints a dismal picture of the first inhabitants of the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation, who were victims of federal government ineptitude and poorly treated.

“The first year of the Oregon reservations was chaotic,” he writes. “The expediency of creating the reservations to alleviate several wars was perhaps too quick and too complex for the federal government to respond with full support. … The lack of preparation of the expenses needed for removal and care of so many Native people was apparent. The many problems created by a sudden change in the living environment for the tribes was also not well understood or anticipated. Few foresaw the problems with nutrition or illnesses, likely caused by exposing remote Indian groups to Tribes from regions hundreds of mile apart.”

“It was really, really horrible how people were being treated,” Lewis says, adding that around 500 Natives “disappeared” in the first few years of the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation. He thinks they either left the Reservation and re-assimilated into the settler culture, or they died from the strange food and harsh living conditions, such as having only a tent between them and the Coast Range winter.

He also draws an interesting through line from the Native Americans’ loss of land and the accompanying intergenerational trauma to the continuing intergenerational poverty of Tribal peoples that continues to this day.

“Tribal people in Oregon today are commonly quite poor, unable to advance into the middle class,” he writes. “The actions of the United States and its citizenry have continually impoverished the Tribes and their people for the past nearly 200 years. Few Native people own land, have access to enough land to practice their culture, or know the history of how their family got to their position.

“This was not the case for the settlers in Oregon. These settler families benefitted greatly from free land and labor for a pittance … They built agriculture, industries, cities, and great amounts of wealth and power for themselves. The descendants who have retained wealth based on their land holdings and the wealth of their pioneer ancestors now have extensive resources that continue to benefit each generation.”

Other interesting historical facts include that Indian Agent Joel Palmer was pressured out of his job because he was seen as too sympathetic to Native Americans’ plight and that Indian agents had to travel to San Francisco to cash a federal bank draft to buy the supplies for the fledgling reservations because there was no bank in Oregon.

“Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley” also features Greg Robinson (Chinook) artwork on the cover.

Ooligan Press is affiliated with Portland State University and staffed by students pursuing master’s degrees in an apprenticeship program under the guidance of publishing professionals. “Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley” is available for pre-order via Amazon and other book-selling sites for $24.95.

“The full history of those who have lived in the Willamette Valley since time immemorial is one that needs to be told,” says Kerry Tymchuk, executive director of the Oregon Historical Society. “ ‘Tribal Histories of the Willamette Valley’ brings to light a heretofore largely untold story of courage and resilience. It should be required reading for all who want to understand the true history of Oregon.”