Tribal Government & News

Interior report on Indian boarding schools includes Grand Ronde site

By Dean Rhodes

Smoke Signals editor

A damning report on the federal government’s 150-year Indian boarding school system released on Wednesday, May 11, identifies nine such schools that operated in Oregon and includes the Grand Ronde Boarding School.

The investigative report is the first comprehensive effort to address the legacy of federal Indian boarding school policies and was the result of Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland implementing the Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative in June 2021. Haaland is the first Native American to lead the Department of the Interior, which includes the Bureau of Indian Affairs and Bureau of Indian Education.

The initiative’s investigation includes a 102-page report as well as a complementary list and individual profiles of the 408 federal Indian boarding schools that operated across 37 states or then-territories between 1819 and 1969. In the Pacific Northwest, Washington state had 15 Indian boarding schools and Idaho had six, the report states.

The most federal Indian boarding schools were located in Oklahoma, 76; Arizona, 47; and New Mexico, 43.

“The content of this document may be disturbing or distressing,” the federal Indian boarding school list cautions prospective readers.

The Grand Ronde Boarding School opened on Oct. 1, 1862, and provided housing and education, and received federal support. Father Adrian Croquet also opened St. Michael’s Catholic Church in Grand Ronde in 1862 and the Interior report examines the complicity of religious institutions and organizations in participating in the Indian boarding school system and how they were often paid on a per pupil basis to “civilize” Native American youth out of the Civilization Fund that received federal funding from 1819 through 1873.

“The Grand Ronde School, which was day-only in the beginning, functioned on the Grand Ronde Agency beginning in the 1860s or 1870s,” the boarding school list states. “For much of its existence, it was run in cooperation with the Catholic Church. Location is approximate and is at Grand Ronde sub-agency.”

The Grand Ronde Boarding School closed in 1908.

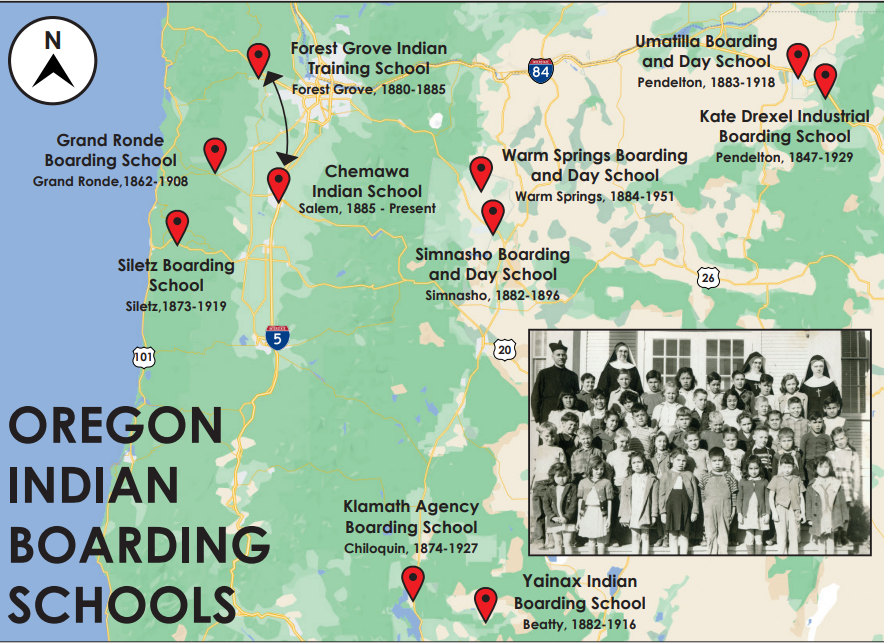

The eight other Indian boarding schools identified in Oregon included the Forest Grove Indian Training School (1880-85), which became Chemawa Indian School (1885-present) in Salem; the Kate Drexel Industrial Boarding School (1847-1929) in Pendleton; the Klamath Agency Boarding School (1874-1927) in Chiloquin; the Siletz Boarding School (1873-1919) in Siletz; the Simnasho Boarding and Day School (1882-96) in Simnasho; the Umatilla Boarding and Day School (1883-1918) in Pendleton; the Warm Springs Boarding and Day School (1884-1951) in Warm Springs; and the Yainax Indian Boarding School (1882-1916) in Beatty, which is located northeast of Klamath Falls.

Map by Samuel Briggs III/Smoke Signals

Federal Indian boarding school policies resulted in the twin goals of cultural assimilation and territorial dispossession of Indigenous peoples through the forced removal and relocation of Tribal children, an Interior news release says.

Through treaties and other agreements, Tribes ceded approximately 1 billion acres to the United States in exchange for such things as health care and education.

In addition to compiling a list of Indian boarding schools, the investigation also identified marked or unmarked burial sites at approximately 53 different schools across the boarding school system. “As the investigation continues, the department expects the number of identified burial sites to increase,” the news release says.

Although the report declined to identify where the burial sites are located, it has already been widely reported that burial sites have been found at Chemawa Indian School in Salem.

The investigation’s initial analysis also estimates that 19 federal Indian boarding schools accounted for more than 500 child deaths. The Interior Department expects that number to increase as well.

“The consequences of federal Indian boarding school policies – including the intergenerational trauma caused by the family separation and cultural eradication inflicted upon generations of children as young as 4 years old – are heartbreaking and undeniable,” Haaland said.

“We continue to see the evidence of this attempt to forcibly assimilate Indigenous people in the disparities that communities face. It is my priority to not only give voice to the survivors and descendants of federal Indian boarding school policies, but also to address the lasting legacies of these policies so Indigenous peoples can continue to grow and heal.”

Haaland said the Department of the Interior will launch a year-long “Road to Healing” tour that will include stops across the country to allow American Indian, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian survivors of the federal Indian boarding school system to share their stories, help connect communities with trauma-informed support and collect a permanent oral history.

According to the Department of the Interior, “there is ample evidence in federal records demonstrating that the United States coerced, induced or compelled Indian children to enter the federal Indian boarding school system.”

The investigative report highlights some of the harsh conditions that Native children endured in the boarding schools, which used systematic militarized and identity-alteration methods in an attempt to assimilate Native American youths. Children were given English names, forced to have their hair cut, discouraged or prevented from using their Native languages or practicing their religions or cultural customs, and were organized into units to perform military drills.

Punishment often included solitary confinement, flogging, withholding food, whipping, slapping and cuffing. Older Native children were often forced to punish younger children in a court martial-like setting. Runaways at the Kickapoo Boarding School in Kansas received whippings upon their return that were administered “soundly and prayerfully.”

Native children also were taken advantage of, having to perform manual labor and taught vocational skills, such as brick making and working on the railroad system, that were often irrelevant to the industrial U.S. economy.

Living conditions also were intolerable with Native children often sleeping two or three children to a bed, toilet facilities that were not expanded proportionally to the increase in students, and diets consisting mostly of starch and sugar and low in fresh fruits and vegetables. Survivors of the system were more likely to have cancer, tuberculosis, high cholesterol, diabetes, anemia, arthritis and gall bladder disease than non-attendees upon reaching adulthood.

The investigative report also identifies next steps that will be taken in a second volume that is being funded by a new $7 million investment from Congress through fiscal year 2022.

Next steps include creating a list of marked and unmarked burial sites at federal Indian boarding school locations, approximating how much federal funding was allocated to support the Indian boarding school system, and further investigation into the legacy effects of the school system on Indigenous peoples today.

In addition to the 408 federal Indian boarding schools, the investigation also identified more than 1,000 other federal and non-federal institutions, including Indian day schools, sanitariums, asylums, orphanages and stand-alone dormitories that may have been involved in the education of mainly Native American children.

Smoke Signals video: Visiting the sites of three federal Indian boarding schools in Oregon