Tribal Government & News

Record-setting service: Chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy becomes longest tenured Tribal Council member

By Dean Rhodes

Smoke Signals editor

Sometime in April, while she was leading the Grand Ronde Tribe as it navigated its unprecedented response to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic that included closing Spirit Mountain Casino, Tribal Council Chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy unceremoniously became the longest-serving post-Restoration Tribal Council member.

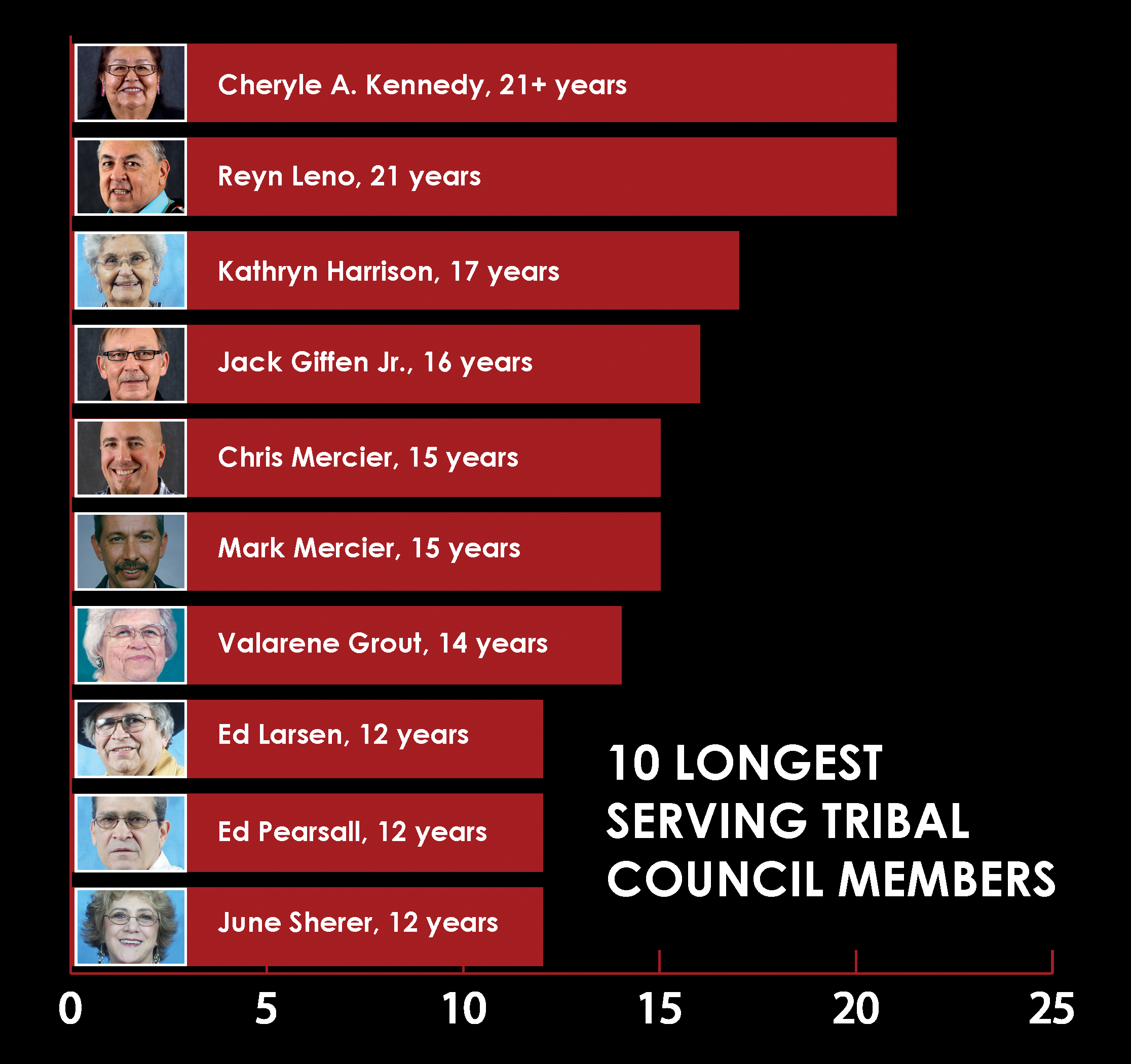

Kennedy, who also turned 72 in early April, served on an early post-Restoration Tribal Council from May 1985 through September 1986 – one year and four months. Add that time to her consecutive years of service starting in September 2000 and Kennedy has surpassed former Tribal Council member Reyn Leno, who served 21 consecutive years from 1996 through 2017.

Kennedy has received more than 3,800 votes during her eight runs for Tribal Council and holds the record for most votes ever received in an election – 712 in 2018. She has been the No. 1 recipient of votes five of the last seven times she has run for Tribal Council and has lost only one recent election, finishing fourth in 1999.

Her service even pre-dates Restoration, having been appointed to serve one year in 1979 on an honorary Tribal Council.

Kennedy also has been elected by her fellow Tribal Council members to the chairwomanship for 13 of her more than 21 years on council.

In between her years serving on Tribal Council, Kennedy worked for 15 years as the Tribe’s health director, guiding the construction of the 40,000-square-foot Health & Wellness Center, and served as executive director of the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board.

Kennedy sat down with Smoke Signals Editor Dean Rhodes on Tuesday, April 21, to discuss her record-setting years of Tribal Council service to the Grand Ronde Tribe. Excerpts of that 36-minute interview are below.

Has the time gone by quickly or not? Did you realize you were even getting close to setting a record?

Kennedy: It’s something that I don’t really think about a lot. For me, I have often been asked, “Wow, Grand Ronde has developed so fast!” That’s not my feeling about it. It’s slow. Serving even during the Termination era on council, we talked about a lot of the thoughts, the ideas, the dreams, the direction the Tribe should go. Laying the foundational pieces so that when we were ready, we could launch forward. So my history has been a lot longer than that, and so from that perspective I don’t think things have moved as quickly as I thought, but I know things take time and planning processes, availability of funds … all of that plays into how fast you develop and move. For me, personally, I have always been on the sovereignty piece. I’m dedicated to making sure that we stand as a sovereign nation. I was always interested, and still am, in getting the foundational pieces for what a sovereign government does.

What are the biggest differences that you see between how Tribal Council operated in the 1980s and how it operates today?

Kennedy: At that time, it was really following the direction of the Grand Ronde Restoration Act, and that was moving forward with securing our first land base and deliberating on what the Tribe should have returned to it. It was a lot of that work and it was meeting with officials, meeting with civic groups, meeting with the federal agencies to determine what lands and making excursions to various sites to see what land base we would acquire. That was kind of a single focus.

The biggest difference that I see is that there is a lot more of what we do now. I think about it as multi-tasking. I have had log truck drivers in my family … and they are often shifting gears. That is how it feels now. You’re always shifting gears. Oftentimes during the day, you’re dealing with maybe a fishing issue and then you’re talking about health and then we’re talking about our governmental role in helping to establish the first federal historical site for this part of the United States. So you’re switching all the time and you have to be in tune. There’s a lot of reading required. You’re always reading and you’re always responding and paying attention to what the environment is on the federal level, the state level, the local level, the Tribal level, and what’s happening here with our people.

You were involved in a serious car accident in the late 1990s that helped you refocus on what you wanted to do and return to service on Tribal Council. Could you explain how that affected you?

Kennedy: I left, I believe, in 1998. I accepted a position with the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board to serve as the executive director there. Things here in the Tribe … I’ll just be honest … politics plays into many things and at the time I had worked at the Tribe, with our Tribal people, with our councils, and health had always been a No. 1 issue for the Tribe. … In 1997, I thought there was some internal strife and I wasn’t really sure what was happening, but I felt that there was pressure to do things in a different way, and at that time the health clinic was established as a health authority, which creates autonomy. We had a board set up and I’m not sure if there was dissension, but I thought, “I didn’t work this hard to bring a quality health care delivery system to our people to have it either disbanded or to be piecemealed out.” If that’s the case, I’ll bow out, and it just so happened that the executive director position at the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board became available and I thought that I would apply for that. It was very competitive, but I was selected. I took that job and worked there for quite two years.

In December … I have family who live over in central Oregon; some near the Warm Springs Reservation and some on it. I was going there for Christmas to take presents over to my sisters and on the way back and I know after years of driving over the mountains, you kind of know you have to get over the mountain when the opportune time is. I knew I had to get out of that area before 4 o’clock because the sun would be going down and it would become icy. But it happened earlier and there was a head-on collision.

I had my grandson, who was 11 years old at the time. It was … you hear the phrase you see your life flash before your eyes and that really happened to me. And I knew the options weren’t great. I was skidding across the ice and I had no brakes and as I was going across the road I saw the headlights of another car coming at me. I thought, “What’s worse? Hitting head-on or going over the cliff?” I would rather stay in our lane, but that wasn’t happening. I just cried out in me, “God help us!” And the last thing I thought was that I have lived my life, but spare my grandson.

When I survived it, I didn’t feel like I would survive it because when we hit and that huge explosion and I felt my body break. I had like 29 different bones that were broken during the crash. I was surprised that I lived. … But the astonishing thing about all of that was that my life was spared for a reason. In my mind, I thought, “Maybe things have to change for me.”

That was in December. It took me a few months to recover and about three, four surgeries later. I always came to General Council meetings, but not during that time I was laid up. But I came to the General Council meeting and someone nominated me. I don’t even remember who it was. I kind of thought, “No, I don’t want to do that. I don’t think I should.” But something in me, I felt like I was being pushed to accept it. … So I said, “I accept” and I was elected. It was time to serve in a different way.

Tribal Chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy met with President Barack Obama in 2010 in Portland at the Oregon Convention Center.

Tribal Chairwoman Cheryle A. Kennedy met with President Barack Obama in 2010 in Portland at the Oregon Convention Center.

Let me just run a couple numbers by you. I know it is difficult to talk about yourself, but I am going to ask you to do that. You have received more than 3,800 votes during your runs for Tribal Council. You hold the record for receiving the most votes in an election at 712. You have been the No. 1 recipient of votes five out of the last seven times you have run for council. What is it about you and how your conduct yourself as a Tribal Council member that elicits that kind of support?

Kennedy: Going through my years of higher education that is a question that has always been studied: What makes a leader a leader? Are they born or are they made? I tend to believe that they are made, that there is destiny and that’s what promotes you.

I was always very shy, a true introvert. In my family and my siblings, I have extroverts who are very gregarious and when they feel good they can dance on the top of a table. They thrive on that; the energy of the people just invigorates them. Not me.

But I look back in my family, and I have four chiefs who signed treaties and I believe that those attributes, whether you know it or not, are being taught to you in your growing years.

You mentioned politics earlier and another number I wanted to run by you is that you have been elected chairwoman 13 of your 21 years on Tribal Council. Was it a difficult time for you recently when you were not the chair for five years?

Kennedy: If there were any difficulties it was really in promoting things that I thought were important to the Tribe. Again, I started with sovereignty. I have always believed that sovereignty is the basis. We had to be solidly in our foundation, so all of the governance pieces for sovereignty had to be in place and, at times, I felt like that wasn’t at the forefront. I think for me that was a bit of a struggle because I know that you govern your own people. That means you also take care of them.

Where does the current problem – the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic – rate as a problem in your 21 years on Tribal Council? Is it the biggest challenge you’ve seen?

Kennedy: No. Termination. When we had N1/HI, which was a few years back, it was the same kind of thing except there was a cure that happened early on or it would have been like this. Very serious. Living through the era of polio, for Tribal people tuberculosis … for me, this one is because public health measures are the cure. It’s so hard for people to abide by them and they take it lightly. I believe we would have had a handle on it if we would have closed at the end of February. I believe it would have been contained, but it was let’s wait and see. If people get it, then we’ll do something. Well, that’s not the right approach.

Is there one thing that you’ve accomplished in your 21 years that you are most proud of?

Kennedy: Truly, the Health & Wellness Center so that our people could have good health, that we could live out our lives and have a quality of life vs. just living. A lot of that is preventive. Ninety percent of our ailments are due to our behavior. Some of us can have wonderful genes, but you can destroy it through some of the bad behaviors that occur. This epidemic is because we want to continue to do what we want and I understand choice, but someplace in there the voice of reason has to prevail.

You also had a birthday on April 3 and you turned 72. Have you thought about how much longer you want to continue serving on Tribal Council?

Kennedy: I don’t look it at like that. You’re there for however long you’re there. … When I was hired for Grand Ronde. When I came back as one of the first three employees hired, my path has always been about milestones and almost prophetic words to me. When I left to go to Burns in 1980, I lived in Madras and I didn’t want to go over there, but I did because of this. I was so distressed about it. I didn’t know what to do. There was this light in the middle of the night and it scared me, but I heard this voice speaking to me. It told me this, “Yes, go and help these people over there so that they can be strong as you are strong. You’ll be there just a little while and then when that is over I will take you to the land I gave to you and your people in the west. And when you go there, you’re going to go in and help possess the land that I have given you. When that’s done, you and your little ones and your people will be at rest.” That is what I heard. … When it’s all done? I don’t know.