Tribal Government & News

Tribe working to uncover history of Fort Yamhill

By Nicole Montesano

Smoke Signals staff writer

In January, the Tribe officially took possession of a piece of its history; the property where the former Fort Yamhill stood in the 1850s.

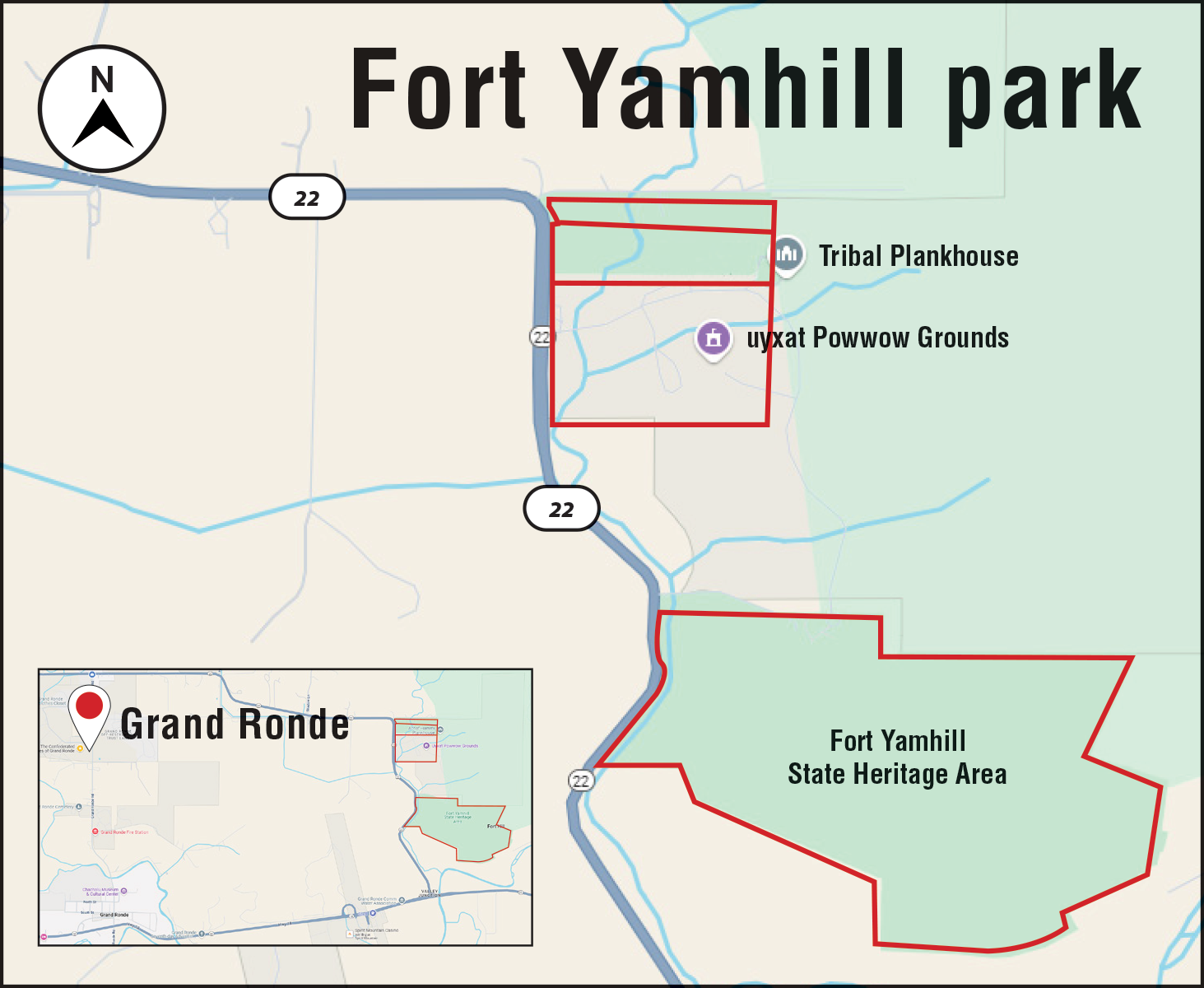

For decades, the 80-acre property had been a missing puzzle piece in the forested hills above the uyxat Powwow Grounds; a state park that Tribal foresters had to work around, memorializing, not Tribal history, but the history of the soldiers at the gate.

The foothills of the Coast Mountain Range had been a hospitable site for the Yamel branch of the Kalapuya for millennia. Deer and elk were abundant and camas thrived in the floodplains, while Oregon white oak nourished wildlife and provided a bounty of acorns. The hillsides offered tarweed seeds, wild carrots, thimbleberries, huckleberries, native blackberries and more. The hill that later became Fort Yamhill commanded a wide view of the valley below.

“It’s a broadleaf tree and grassland area, protected from the east winds, with water access; this is a great place,” Tribal Historic Preservation Office Manager Briece Edwards said.

In the 1850s, the U.S. Army drove Tribes from across the Willamette Valley and southern Oregon to the new Grand Ronde Reservation, jamming together people with different languages and customs without regard for their differences. In 1856, the Army built a fort on the hill above to ensure everyone stayed put. It was also supposed to be used as a safeguard to keep white settlers from murdering the Reservation’s inhabitants.

But with the U.S. government focused on the Civil War in the South, the fort was decommissioned just 10 years later. The Tribes stayed and cherished what they could retain of their varied heritage.

In 2006, the state declared the property a park and the Fort Yamhill State Heritage Area was listed on the National Historic Register. Little remains of the fort, except for the information plaques lining a winding uphill trail, a restored historic officer’s house with a uniformed dummy in the window to provide ambiance and scattered non-native vegetation. Over the years, various archeological digs have sought information about the fort’s history.

“What’s important is not just the 10 years of being a fort, but all the years before that and after that,” Edwards said.

Now, with the property in the hands of the Tribe, its archeologists can explore that rich history, focusing on the viewpoints of the inhabitants, rather than the invaders.

Archeologist and Tribal member Sharrah McKenzie is using ground-penetrating radar to map the fort’s buildings in a roughly 8-to-10-acre area. But Edwards said the Historic Preservation Office hopes McKenzie’s work will enable them to create a temporal as well as a spatial map showing things such as where the Yamel people built their camas ovens long before the settlers arrived.

Tribal Lands Department/Self-Governance Manager Jan Reibach has presided over numerous land transactions over the years, but this one was unique.

Shortly before 2020, Reibach said the state Parks and Recreation Department offered to transfer the Fort Yamhill property to the Tribe, on the condition that it maintain the property as a public park.

“We are responsible for all land acquisitions of the Tribe, regardless of purpose. … we have a Tribal Realty Program with the Tribal lands that administers all of it,” Reibach explained. “So, it came to us because it’s land acquisition even though it’s a donation or a transfer.”

Things went well initially but the hand-off proved unexpectedly complex. A transfer from the state Parks and Recreation Department to a Tribe had never been done before in Oregon, Reibach said.

“In 2022, when we completed our due diligence and were getting ready to transfer the property, they were like, ‘Oh. We can’t do it legally; it’s never been done before in the state and it’s going to require new legislation,’” he said.

Department staff worked with the state to write what became House Bill 2737, then lobbied state legislators to pass it.

After two years the bill finally became Oregon Revised Statute 270.030, which stipulates that “a state agency may transfer, convey, donate, exchange or lease to an eligible Indian Tribe … any real property or interest in real property owned by the agency at such price and on such terms as the agency may determine.”

Meanwhile, the Tribal Lands Department worked to assess the property and draft a management plan.

The transfer was finally completed in January.

“We’re all celebrating this historic project, because there’s no one better to take ownership of this historic land and bring healing, than the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde,” Reibach said.

He’s now working with Tribal Communications Director Sara Thompson and Tribal Council Chief of Staff Stacia Hernandez to plan a commemorative event for the property.

The Tribe also plans to rename it, he said.

“It will be a name that honors the Tribes, while it maintains an openness to the community as well,” he said.

Tribal Natural Resources Department Manager Colby Drake said he’s enjoyed the way the property has brought several different departments together to work on the project.

“It gets us out of our silos and working with other departments, which we don’t get to do very often, and gives them the same opportunity with us,” he said. “I think it’s a great opportunity for the Tribe.”

Drake noted that the park remains open for day use under the management of Tribal Parks and Recreation Coordinator Jerry Bailey.

“We want this to be available to Tribal members and Oregon citizens,” Drake said. “I feel like we will get a lot of requests from a lot of school districts and local schools for tours that will bring in the Cultural Resources (Department) to talk about the property’s historical significance.”

The Tribe also hopes to improve the informational plaques at the site, which focus on the soldiers at the fort, Drake said.

“It’s a neat opportunity for Grand Ronde to have a … Tribal park, where we get to tell our story,” he said. “We are the main characters, the main story. I’m really excited about that.”

Historically, archeology has been conducted more to the detriment than the benefit of Indigenous people, leaving many feeling bitter.

It was often done by, “people that didn’t belong to these cultures and would have their own interpretation without talking to anybody from these Tribes or anybody local. … It was oftentimes just taking artifacts and removing from their homelands and putting them into museums or universities,” McKenize said.

The Tribe is teaching a more inclusive and respectful approach, encouraging archeologists to focus on learning what the items they find are and how they are used in context, rather than taking them away to a museum or laboratory.

“It doesn’t have to be about just digging holes,” Edwards said.

The Tribe is pursuing its archeological research with as little digging as possible, using technology like ground-penetrating radar.

Rather than referring to “artifacts,” Edwards said, the Historic Preservation Office uses the word “belongings,” to emphasize that items had and may still have importance to living people.

The mapping project provides a guide, rather than definitive answers. Ground-penetrating radar reflects denser and less dense areas. What it shows, Edwards said, are underground anomalies, that are different from the surrounding soil. It’s not always clear, however, what they are.

“Everything is an anomaly,” Edwards said. “Is it a square anomaly, a round anomaly, a blob anomaly?”

With those shapes mapped out on paper, however, researchers will be able to see the outlines in relation to each other and start trying to determine what they are.

“We want to start a landscape scale; how does this fit with the larger area of the Grand Ronde Valley,” Edwards said. “We think we know where the historic buildings of the fort were, but we’re also looking for … things that predate the fort or came after it.”

In addition, Edwards said there is an interest in inviting people in to tell their family stories about the area.

The process will take another year or more to finish the mapping. “Ground penetrating radar is a slow process,” Edwards said. “A lot of coordination has to be done, making sure areas are mowed, so you can use the machine, because if you’re not making contact with the ground, the radar just bounces off the surface. And then there’s the things you don’t plan on. In 2020, the western half of the state was on fire, and there was a little thing called the pandemic. Then (in 2021) we had the ice storm …”

The machine can only be used during good weather, but the crew will use the rainy months to run a computer program analyzing and mapping out the summer’s findings, overlaying them with historic maps and reviewing the data.