Culture

Still seeking answers: Tribal member Heather Cameron has been missing for five years

By Danielle Frost

Tonya Gleason-Shepek drove to Grand Ronde from her home in Happy Valley, some 57 miles away, to address General Council on Oct. 1, which also marked the beginning of Domestic Violence Awareness Month.

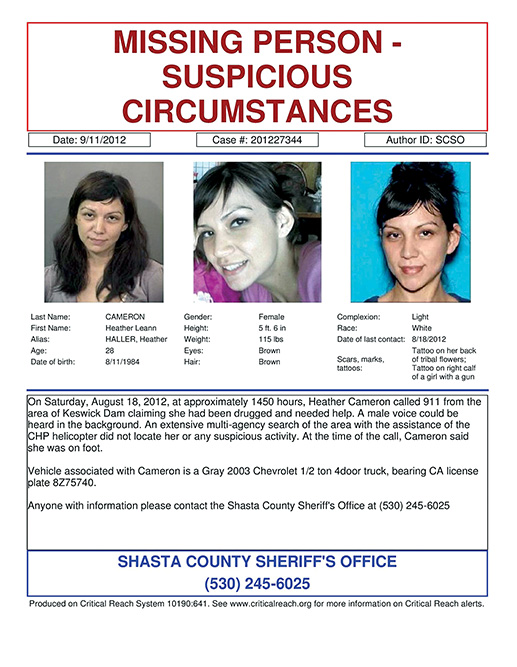

In her hand she clutched a missing person flier. The woman on the front is her cousin, Heather Cameron, missing since Aug. 18, 2012, from a remote area of Shasta County, Calif.

Cameron had recently celebrated her 28th birthday and had four young children – three daughters and one son. She is a Grand Ronde Tribal member and has family living in Oregon.

“I am asking you to remember her story,” Gleason-Shepek said, her voice shaking. “She was a victim of domestic violence. …We remember Heather every day. We may never be able to bring her home and lay her to rest, but we will never give up. When I look at Heather’s face, I see the faces of all of our Tribal members who are enduring domestic violence, depression, addictions and suicide.”

Gleason-Shepek said Cameron’s story mirrors those from Indian Country, where 84 percent of Native women have experienced domestic violence.

“I ask you to choose mental health as a (budget) priority,” Gleason-Shepek said. “Mental health is our most underfunded, unmet need in Indian Country. Heather’s life was precious. She mattered. Everyone in our Tribal family that is high risk, they matter, too.”

When contacted later, Gleason-Shepek said that Cameron was last been seen with her ex-boyfriend, Daniel Lusby, and that the two were heading to Keswick Dam, a remote area 20 minutes outside of Redding, Calif., near the Sacramento River and Shasta Dam.

“It was the last time anyone heard from her,” Gleason-Shepek said. “She wasn’t dating him any longer, but they were still in the same circle.”

Lusby’s criminal record in Shasta County Superior Court shows that he has been charged with nine felonies since April 2012, four of which were reduced to misdemeanors. The Sheriff’s Office confirmed that Lusby had been in custody at the Shasta County Jail 11 times.

Lusby also spent time on Shasta County's Most Wanted list until he was arrested in 2015. Additionally, an article in the Porterville Recorder noted his arrest for car theft, stolen property and possession of methamphetamine in November 2012.

Cameron also had a criminal record in Shasta County, which included three felonies, two of which were reduced to misdemeanors.

Family members recall that although Cameron struggled with substance abuse, she was a good mother who regularly saw her children no matter what else was going on.

“Her life mattered,” Gleason-Shepek said. “Whether or not she used drugs isn’t the point. She has three little girls growing up without a mother. It breaks my heart. Five years is a long time not to know.

“I just hope our Tribe becomes interested in this issue and breaks these old thoughts that domestic violence is a family issue. It’s a community issue. I want to raise awareness and increase justice, and show people that we honor and respect the sacredness of our women. As I reflected on my time on Tribal Council, (not being able to do so) has been my biggest disappointment.”

The day she disappeared

On Saturday, Aug. 18, 2012, at approximately 2:50 p.m., Cameron called 911 three times from Lusby’s cell phone near the Keswick Dam area, claiming she had been drugged and needed help. A male voice could be heard in the background.

Police conducted an extensive, multi-agency search, according to the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office. Lusby was interviewed as a primary person of interest in the case.

“He was (formally) interviewed on three occasions, but never arrested,” said Shasta County Sheriff’s Office Sgt. Brian Jackson. “He is still a person of interest and this case is still open. … There is still information we are trying to corroborate.”

Lusby was last interviewed in April 2014. When he was asked why Cameron used his cell phone to call 911, he told police that she had walked off and had taken the phone with her, Jackson said. The cell phone was never recovered.

Jackson said that the location Cameron called from was remote, with steep hills and canyons, and cell phone reception was poor, resulting in the multiple and dropped calls to 911.

After an initial search, which included all-terrain vehicles from the Bureau of Land Reclamation and a California Highway Patrol helicopter, Cameron was not found, nor was there any evidence of suspicious activity, according to the Sheriff’s Office.

On Sept. 4, 2012, almost two-and-a-half weeks later, Cameron was officially reported as missing by her estranged husband to the Redding Police Department, which referred the case to Shasta County.

“Our office then began a missing person’s investigation and multiple searches of the area the following week,” Jackson said. “Family members also went out and did several searches with ATVs and on foot. She is still a missing person, the case is still open and other suspects have been excluded. We want to find out where she is, so we continue to do follow up on any information we receive.”

Cameron’s cousin, Shannon Hauberg, created a Facebook page, Find Heather Cameron-Haller, soon after she went missing. Cameron also is listed as a missing person by the Shasta County Sheriff’s Office and on the National Missing and Unidentified Persons database.

Additionally, Cameron is one of 2,033 missing people from California profiled on the The Charley Project website, which has approximately 9,500 "cold cases” from across the United States. There is currently a $5,000 reward being offered for information that leads to solving her case.

“Heather wasn’t given a very good chance at life,” Hauberg said. “Her parents struggled with drugs and alcohol. She went back and forth between Grand Ronde and Redding.”

However, Hauberg recalls fond times with her when they were children, growing up in rural Redding.

Hauberg and Cameron spent their summers riding in dune buggies, fishing, boating and participating in other outdoor activities.

“She knew the area very well,” Hauberg said. “We were pretty Native kids. My grandma used to call us ‘Pocahontas.’ We loved to wander around in the woods and be in nature.”

On the day Cameron disappeared, Hauberg said she had recently checked herself out of a drug rehabilitation program and was picked up by Lusby. It was the last time anyone confirmed seeing her alive.

“The whole family is struggling,” Hauberg said. “Heather was always in contact with her children’s fathers, so when they didn’t hear from her, we knew something very bad had happened. I remember her as being a great mom and very family-oriented.”

Lusby did not respond to several attempts by Smoke Signals, including a phone call to his place of employment and a Facebook Messenger message, seeking comment on Cameron’s disappearance.

Violence part of larger issue

A Cheyenne proverb states: “A Nation is not conquered until the hearts of its women are on the ground. Then it is done, no matter how brave its warriors or strong its weapons.”

It is particularly telling when one looks at national statistics regarding missingand murdered Native American women.

Under the 2005 Violence Against Women Act, a national study authorized by Congress found that between 1979 and 1992 homicide was the third leading cause of death among Native females aged 15 to 34, and that 75 percent were killed by family members or acquaintances.

Title IX of the act required the National Institute of Justice to conduct a national baseline research study on violence against Native American and Alaska Native women, including domestic violence, dating violence, sexual assault, stalking and murder, evaluate the effectiveness of federal, state, Tribal and local responses to violence against these women, and propose recommendations to improve the effectiveness of responses.

The report, released in May 2016, found that 84.3 percent have experienced violence in their lifetime, including sexual, physical, stalking and psychological aggression. Also, 39.8 percent have experienced these types of violence in the past year.

Compared to non-Hispanic, white women, Native American and Alaska Native women are 1.2 times more likely to have experienced violence during their life, and 1.7 times more likely to have experienced it during the past year, the study found.

The study further found that medical care was the most common service needed by the victims of lifetime violence. Among the women seeking services, 38 percent were unable to get the help they needed.

Grand Ronde Domestic Violence Prevention Coordinator Anne Falla said that intimate partner violence is not always limited to just physical abuse.

“Abuse is also emotional in nature and it is easy to discredit people who report it by making them look bad,” Falla said. “For example, people will say the person making the claim has dementia or blame past drug use, even if it was 20 years ago. It is really hard in this region as well because those types of comments live on with a person. … So it is hard to climb out of that and they are not seen as credible.”

Shedding light on domestic violence can be difficult even in professional settings. Despite the recent reports that indicate that Native American women experience more intimate partner violence than any other ethnic group, Falla has noticed pushback.

“Until a few years ago, there were no statistics,” she said. “So part of this is raising awareness. Native Americans get forgotten when it comes to reporting. If you’re trying to disclose (a crime), law enforcement sometimes really doesn’t know who to give you to. In some situations with my clients, it has taken months for them to be able to tell an officer, then they didn’t get a good sense that they would get anywhere or that … the situation was credible.”

Other issues that domestic or sexual violence victims may face is feeling as if they lack credibility due to past history or unfavorable experiences with police or the courts.

“There is a lot of extreme fear, embarrassment and shame,” Falla said. “But there are people who will believe you and ultimately understand.”

To help combat the problem of where to report, the U.S. Department of Justice created a Tribal Access Program, which provides federally recognized Tribes the ability to access and exchange information with national crime databases for civil and criminal offenses.

Tribal governments can access federal crime databases with information, such as criminal background records, outstanding warrants and domestic violence protection orders. The only Oregon Tribe selected to participate was the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

Priority was given to Tribes that had a sex offender registry in accordance with the Adam Walsh Act and that are currently unable to directly submit data to national crime information databases.

The problem of missing and murdered Native women has become so prevalent that the U.S. Senate signed a resolution designating May 5 as the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls.

The resolution states that Native women face murder rates that are more than 10 times the national average and that little data exists on the number of missing Native women in the United States.

“Often, these disappearances or murders are connected to crimes of domestic violence, sexual assault and sex trafficking,” states a press release from the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center.

As far as Cameron’s case goes, her family is seeking resolution to a life-altering event that has haunted them for more than five years.

“Heather can now be legally declared dead,” Gleason-Shepek said. “So the next step for the family is to educate ourselves on the California legal process and determine if we are able to navigate it ourselves or if we will need to raise money to hire legal assistance.”

Once Cameron is declared deceased, the Tribe will release her monies to a designated guardian of her estate, Gleason-Shepek said.

“We know that Heather would want her children to have this money,” she said. “We hope to use some of the money to increase the reward (for information) and the remaining money would go to her children.”